Mao Harada (Japan)

Mao Harada appears to be part of the first generation of Japanese architects that are aware of the inherent limitations of modernism, and as such, understands architecture and the city not as outcomes of a unique sequence of logic and reasoning but as a complex, sometimes contradictory, and always non-deterministic organism.

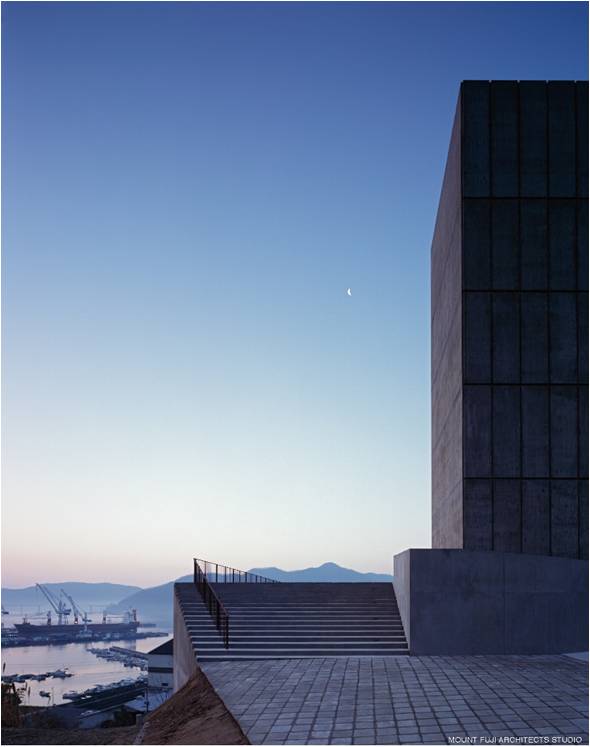

With the Mount Fuji Architects Studio, founded with Masahiro Harada, she has developed a series of works in which the primary parameters of architecture – geometry, structural mechanics, materials, and construction – arise from the constant confrontation between two great entities: nature and society. In the restoration project of a former industrial complex on the coast of Seto in Fukuyama, Hiroshima (2013), the extensive flat surface of the main residential building’s roof is treated as a public space, with a great urban sensibility. www14.plala.or.jp/mfas/mfas.htm

With the Mount Fuji Architects Studio, founded with Masahiro Harada, she has developed a series of works in which the primary parameters of architecture – geometry, structural mechanics, materials, and construction – arise from the constant confrontation between two great entities: nature and society. In the restoration project of a former industrial complex on the coast of Seto in Fukuyama, Hiroshima (2013), the extensive flat surface of the main residential building’s roof is treated as a public space, with a great urban sensibility. www14.plala.or.jp/mfas/mfas.htm

CANDIDATE VISION

“Dialogue” between the old and the new “substance“ I do not subscribe to the assertion that “the city is a problem and architecture is the answer.“ That point of view is a pure product of modern architectural theory, which as such weighs very heavily on today’s architectural education programs: What are the problems running through the city? What answers can architecture offer them? School trains us in the acquisition of this method of questioning. Student evaluation is based on this conceptual and rational system of question and answer. And it is doubtlessly relevant, if limited to academic training; architecture on paper, devoid of substance, remains at a level of abstract purity that allows it to theoretically resolve the problems posed by the city. But with real architecture it is quite another matter. Indeed, even when it is designed as a pure answer, architecture realized, from the moment it imposes “mass” and becomes a built object, never manages to get beyond the “city=problem” equation. Because many architects have not grasped the obviousness of this, an incalculable number of buildings have sprouted in the urban landscape through the conscious application of the lesson learned: “problem-solution.” Unfortunately, the legitimate and equitable “answer” expected often winds up being nothing more than deplorable “urban filler”. For in using this approach, the concrete situation of the city is rendered abstract, theorized and formalized as problem and turned into a set of logical systems, which will in turn administer a logical architectural answer. We are doubtless the first generation to become aware of the reality of modernism’s limits. We sincerely and conscientiously avoid dealing with architecture through concepts as much as possible. For us, the city is from the outset imbued with “substance,” and the architectural process is the creation of “substance”. Therefore, we seek to manipulate these concrete relationships, as they are, in all their concreteness. The relationship between pre-existing city and future architecture is never envisaged in a unilateral way, as one would do when bringing an answer to a question, but rather as a continuous and balanced “dialogue” between the old and the new “substance”.

PROJECT DATA

SETO

Location: Fukuyama, Hiroshima, Japan

Project Type: New construction

Use of the Building: Company house

Construction Period: October 2011 – March 2013

Awards: 2014 JIA Chugoku Architecture Award 2014, Award of Excellence • 2014 Nichijiren Architectural Award, Award of Excellence • 2014 Iconic Award (GER), 1st-Prize • 2014 LEAF Awards, Residential Building of the Year (UK), Multiple Occupancy, 1st-Priza • 2014 German Design Award 2016( Germany) Winner • 2015 14th Yoshinobu Ashiwara Award

Housing for a shipbuilding company on a cliff overlooking the beautiful and calm Seto Inland Sea, where small islands float. This project is expected to revitalize a local industrial city while providing comfortable accommodation for 37 families. On the roof that extends from ground level uphill is a rooftop plaza, a rare public space in the hilly townscape. The town sits on a steep hill. On the hilltop are village forests, downhill the ocean. The lack of flatland deprived the residents of enough public space to gather and hold events. Taking advantage of slope topography, we tried to create a public space architecturally. We planned a three-layered structure for habitation, half overhanging a cliff. The rooftop with a superb view of Seto Inland Sea has direct access from the north road via a large stairway, and is made open to the public as a rooftop plaza. Under the overhang is another public space with a covered atmosphere that shelters people from the rain. Two light courts reminiscent of Chinese cave dwellings are used as paths to move down to the residential area. They let light and breeze into an otherwise dreary central hallway and drastically improve lighting and ventilation there and in each room. A shape like a ship awaiting its launching ceremony is not just a design. It is a figure that embodies true balance of architectural autonomy, that meets the requirements of the city, environment, structure and economy, and responds with a ship, an object that finds its identity in “balance”.

Credits Mount Fuji Architects Studio

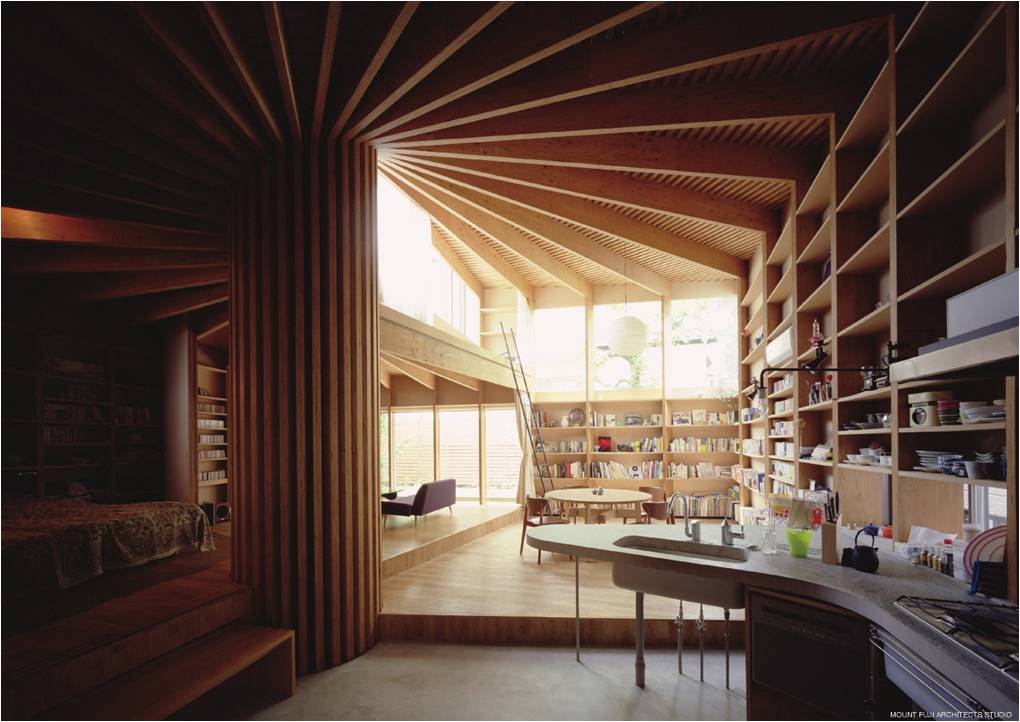

TREE HOUSE

Location: Itabashi, Tokyo, Japan Project

Type: New construction

Use of the Building: Private residence

Construction Period: April 2009 – October 2009

Awards: 2010 RECORD HOUSES Architectural records( USA) • 2010 Annual Residential Space Award • 2010 Modern Decoration International Media Prize(CHN)

This is a house for a couple of young editors in a typical residential area of northern Tokyo. The site is closely surrounded by neighboring houses in all directions. It seemed difficult to open the house horizontally. Normally, this site-type is avoided for housing due to the shortage of natural light and privacy. But we found one unique potential with this dusky site. Its “centripetal tendency” due to its horizontal limitation. So we selected a system of polar coordinates as the architecture geometry instead of the Cartesian coordinates generally used in architectural design. The rule is very simple. Each LVL-frame was rotated and reproduced by 11.25 degrees. And every frame is 55mm higher than the next one. As a result, a strong rational structure resembling a large big tree was realized. The main space is divided to 4 different spaces by the Tree-like column. The spaces all have different heights and widths and different amounts of light. So we imagined how these space characteristics would be used; for example, the high well-lit space is for dining, the low and dim cozy space is for sleeping. In this house people will find their favorite space by themselves, not from named rooms with functions. This old song express my concept simply and correctly. “Under the spreading chestnut tree. There we sit both you and me. Oh how happy we will be. Under the spreading chestnut tree.” (UNDER THE SPREADING CHESTNUT TREE) I wondered whether we could realize the space created by this song in Tokyo. Now I remember that dividing space with a symbolic central column is very traditional in Japan. Many old houses use this system. Maybe this is one reason why the old grandmothers in the neighborhood like this very modern house. The geometry changed the roof into an interesting terrace. Normally it is difficult to create a comfortable garden in this kind of situation. Here, there is a sunny open terrace on the roof.

Credits Mount Fuji Architects Studio

VALLEY RESIDENTIAL BUILDING

Location: Sizuoka, Japan Use of the

Building: private residence

Construction Period: 2010 – 2011

A New Topology The site is long and narrow, running fifty meters north and south, at four to five meters in width, switching back twice. Located in the center of a prominent city that serves as the prefectural capital, it is densely surrounded by mid- to high-rise reinforced concrete buildings as part of a fire prevention zone. The site presented itself as a valley amidst the mountainous residential structures surrounding it. What we were attempting was to regard the existing urban features as a landscape in which, by way of architecture that enhances the topological characteristics of the area, a qualitatively more optimal environment could be realized.

Our design approach was simple. Three stretches of rugged reinforced concrete walls of differing heights, low, medium, and tall, were juxtaposed within one another, conforming to the unusual outline of the site, substantiating its valley-like attributes, and creating a terrain suited to a permanent residence; a transitory structure that enforces a new topology on the permanent environment, protecting the living domain from external noise and gaze, while maximizing the limited sunlight available from above. The north-south expanses give rise to three elongated apertures that establish open areas. The white-plastered interior is segmented, the midsection functioning as a light court containing a shallow pool, with adjacent dwelling rooms on either side. The spaces remain deliberately open-ended. These “frayed ends” produce two areas of emptiness that infiltrate the three functional regions of the house. The perceived effect is one of expansion, counteracting the narrowness of the building imposed by the constraints of the site. The overlapping of discrete areas via these voids creates a mixture of spatial sequences, furthering the impression of passage through a valley.

In addition, the “frays” that constitute the endpoints of these spaces counterbalance the physicality of the mass of concrete that faces them, facilitating its intervention in the space. With this physicality at its core, a sense of “place” suffuses the contours of the interior, overlaying the void spaces, completing them, and establishing an environmental “unevenness” where functions that cannot be created out of neutral space alone are introduced, perhaps offering residents a feeling of ease and attachment to the dwelling that nourishes their psychological orientation within it. The frays slightly disrupt the borders of the site, as well as the distinctions between inside and out, and they promote an atmosphere of shared presence amongst the residents. This architecture, which doesn’t seek to draw itself apart from the surrounding city, possesses an open-heartedness that is also imparted by these “frayed ends”.

When I returned to the residence one morning a month after completion for a photo shoot, I spotted a wild bird bathing in the courtyard pool. It would seem that to a bird, human architecture is no different from a rocky mountain perch or a stream in the valley. The key question is whether it is a good place or not. This is similarly and fundamentally true of humans and all living things. The significance to us of any given open space, as based on social acknowledgment, may change in meaning as culture changes. But the innate recognition of a “good place” will maintain its universality over time, unless there is a change in our physical bodies. It was at that moment that I grasped that what we had been striving for was a “new urban topology” that would exist not merely as the container of open “space”, but as a life-generating “place”.

Credits Mount Fuji Architects Studio

XXXX HOUSE

Location: Yaizu,Shizuoka, Japan,2003

Project Type: New construction

Use of the Building: Atelier

Construction Period: March 2003 – September 2003

Awards: 2003 SD Review, Grand Prix • 2004 American Wood Design Award, Honor Award • 2007 international works • 2007 The Barbara Cappochin Prize for Architecture(ITA)

The automobile is the rival to beat.

One day a client arrived and offered us a deal. He wanted an atelier that could also be used as a gallery to present his ceramic artworks, which he made for pleasure.

With a total budget of just 1.5 million yen (11,000 euro), which he had originally saved to purchase a business-purpose Toyota Corolla sedan, we started our project.

1.5 million yen. A ridiculously small sum of money for building any kind of architecture. Yet a good sum to pay your way in everyday life. It can buy you a “mobile room” with fancy air conditioning, a sat nav system and power windows. A question arose. Are we sure we can properly translate money into the quality of architecture? Can objects that embody beauty and rationality ever be born in such an architectural world, which is highly specialized and socially defined? These concerns had bothered us for years. That’s why we were so strongly attracted to the small budget our client offered.

To beat an automobile in value by conducting a thorough investigation into the closed payment structure of the architecture industry; to create a highly rational and reasonable object by treating an architectural structure as a plain object…

The motto of this project was: “Make great use of 1.5 million yen, and architecture gets ahead of the automobile”.

Credits Mount Fuji Architects Studio

BIOGRAPHY

Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture ( JAPAN), 1976

Mao Harada was born in the residential area of suburban Tokyo and raised in a traditional timber Japanese house that was not as commodious as other buildings in Tokyo. Since childhood, under the guidance of her father (a parabolic antenna designer), it was the place where she started to do some sequential work with a society, such as thinking of her own environment, building up and then returning to the environment. The real knowledge about things and a passion for production open to environment became the foundation of her architect career.

In 1999, soon after graduation from Shibaura Institute of Technology, she attended a workshop on constructing architecture with ordinary materials from the organizational side, carrying out art education activities for adults and children. In 2004 she established MOUNT FUJI ARCHITECTS SUTDIO with Masahiro Harada. Many architecture projects were built with a deep understanding of the raison d’etre of architecture, of the “requirement of nature” and the “requirement of society”, in terms of geometry, structural mechanics, materials, and construction.

The early XXXX project applied a continuous X-shaped frame geometry. It was an ingenious response to budget and time constraints, which produced an elegant architecture. The Tree House also testifies an understanding of materials stemming from a love for nature in co-existence with rationality.

The focus on the organization of things, apparent in the small early projects, was universally shared by the architecture industry, and was an inducement to efficient performance in larger-scale projects. For example, when confronting various issues arising during project development, her view on the basis of rationality in nature was a key factor.

These characteristics were further developed and applied during the exploration of architecture open to both society and environment in more recent works: SETO, shore house, the under-construction building complex as a reboot of local culture (local shop, meeting place, rest space, cafe). Currently, she engages in lateral-scale architecture-centered design activities, such as reconstruction planning after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, and product design using traditional techniques.