The Winner

Jennifer Siegal

“Innovation and unconventional thinking are both hardwired into my DNA. This shows in my body of work and research that questions everything, particularly the static, heavy, inflexible architecture that we somehow still expect in a world that is anything but. In 1998 I named my firm Office of Mobile Design, a nod to my obsession with the transitory. The firm focuses on portable, demountable, and relocatable structures, from homes to schools to stores. It also explores prefabrication, taking advantage of industrial processes to create a more efficient and nimble architecture. Wheels are an important part of OMD’s design approach, examining ways that any city environment can be made more usable and more dynamic if it can be hitched-up, towed, pulled, or driven from place to place. For me, mobility is not about erasing everything that exists, but adding to the infrastructure in a more environmentally sound way — a more intelligent way of inhabiting the landscape — resting lightly on the ground. My firm has developed a reputation not only for hands-on research, but for rethinking already radical ideas. My architecture is not just a “nod to the fantastical past,” like the visionary ideas of Archigram, the Metabolists and Ant Farm. The utilization of the existing industrial vernacular to create the new is a key element in OMD’s work.”

The winner attended the award-giving ceremony and when the prize was announced she said: “Receiving the arcVision Prize is the most important moment in my career and is also much bigger than me. It is for the women that stand beside me and for the women in history who carved the path and created a space in which we are all now recognized for our work. Thank you to the accomplished members of the selection committee and the impact that this award will have on future generations of women to come.”

Honorable Mentions

Pat Hanson

“Architecture is the material realization of an idea. Whether the built form is infrastructural or shelters a community program, the project needs to aspire, in however an elemental way, to rise above the mundane or merely satisfy the functional. Every project begins with an idea, or better a concept that is informed by past projects and preoccupations, but is tethered to the material world or environment of the new project. To arrive at a durable and rigorously conceived architectural idea requires relentless focus throughout the entire building process.

Architecture should be experienced, force attention beyond repetitive habit, because it can engage and transform everyday use. From the perspective of my practice, working within Canadian cities and landscapes, the formidable challenge is the culture of building that is resigned to realizing the functional. Architecture must push against such limitations, to find that moment within the project where the clarification of an idea, whether driven by material or site, will force attention beyond the habitual or resignation.”

Elisa Valero Ramos

“I am interested in living space, landscape, architecture for children, sustainability, precision and economy of expressive resources. I am more interested in consistency than in genius, in coherency than in artistic composition. I am interested in architecture rooted in the earth and in its own time. Although it is no longer fashionable to speak of serving, I believe that an architect’s work is a quintessential service intended to make people’s lives more agreeable—a noble calling that seeks to make the world more beautiful and more human and to make society fairer. Architecture is no place for the nostalgic; it is a job for rebels. In the last ten years I have been engaged in two areas of research. One is focused on low-cost construction systems for buildings with almost zero energy consumption. The technology to achieve high-efficiency houses is already available but too costly for the average person. We are developing a new construction system called Elesdopa (the Spanish acronym stands for double-shell structural system). Its remarkable technical and economic efficiency has already been proved. The second is about the factors that lead to early motivation in youngsters. Architecture for children looks for the best possible means to improve their future, which is the future of the world.”

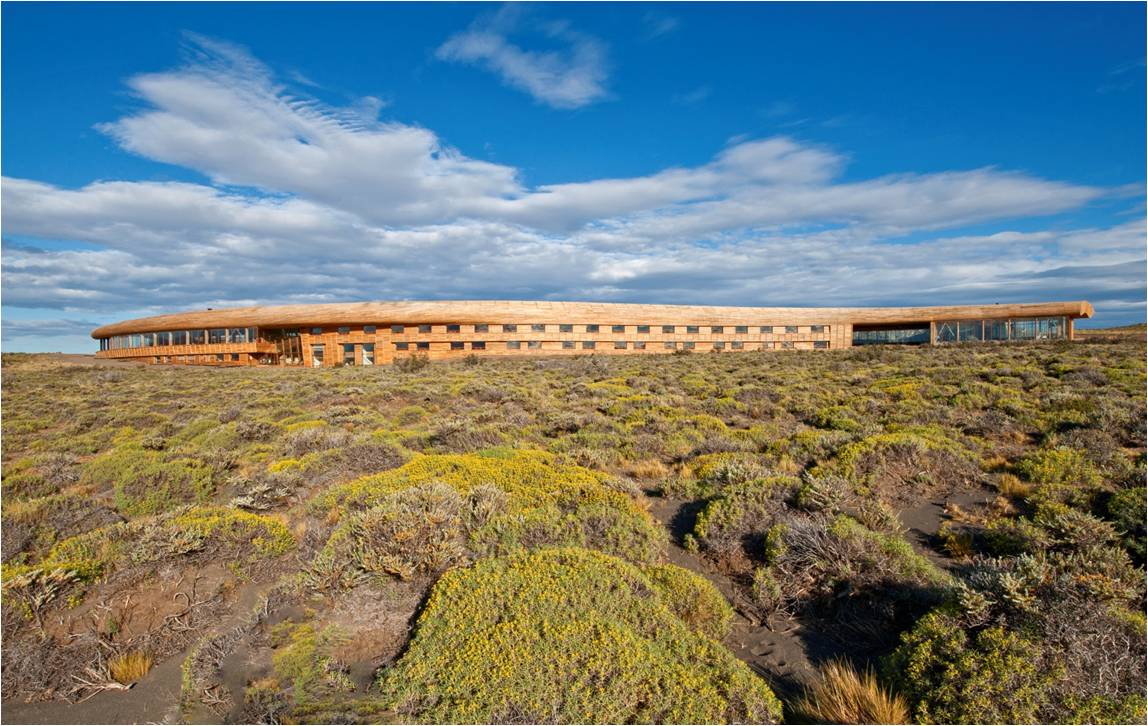

Cazú Zegers

The firm suggests a different take on Chilean architecture, searching for an expressive architecture closely related to Chile, its territory, landscape and vernacular building traditions. Hence, the work developed by the firm is a “work in progress” , which involves a poetic reflection on the way we inhabit the territory, to find new forms. The firm’s unique way of undertaking the design process through the relationship between poetry and architecture comes from the Amereida Thesis*. The thesis states that on his way to India, Christopher Columbus found America as a gift, thus inviting us, the inhabitants of America, to build a new language with shapes that correspond to our “Latino” heritage, accepting ourselves as a new culture, and to dialogue with global paradigms from this source. Cazú responds to this invitation with a “light and precarious inhabitance”, meaning low-tech architecture with high expressive impact, which understands that the greatest asset of Chile and Latin America lies in its territory: “before being a country, Chile is landscape” (N. Parra, Chilean poet). Therefore, she believes that the development of Chile should be based in sustainable tourism, driven by the “original indigenous inhabitants”. Cazú’s work is based on this premise: “Territory is to America, as monuments are to Europe”. Hence, her architecture is not looking to take the lead, but to be a gentle and loving addition to nature.

*Epic collective poem, published by the School of Architecture UCV 1967.

PhotoCredits Hotel Tierra Patagonia: photographers Pia Vergara, Morten Andreson, James Florid, Christian Spies; Whisper House: photographers Isabel Fernandez, Ana Maria Lopez + Emerald House: photographer Cristobal Palma; Kawelluco Rulralisation: Carpa house – photographer Carlos Eguiguren, Cube House, Barn House e Cascara House – photographer Guy Wenborne.